Greg Funnell and Amanda Barnes ride, swim and drink mate tea with some of Argentina’s most skilled horsemen, travelling from the north-eastern wetlands to the faded gaucho heartlands of La Pampa and Patagonia.

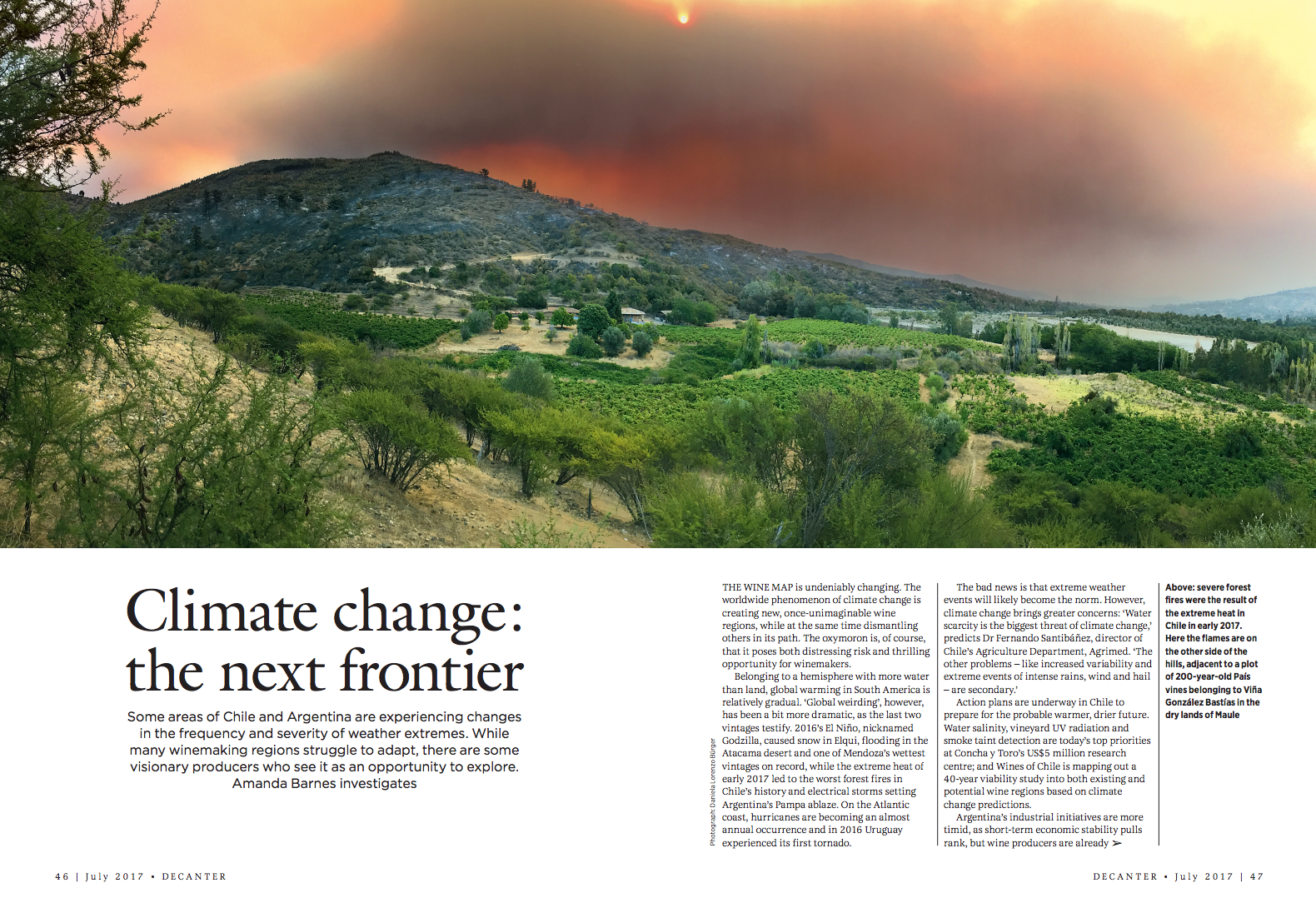

By Amanda Barnes, photography by Greg Funnell: The Guardian, April 2019

The water reaches up to my knees as a large lump rises to my throat. I clench my inner thighs tighter around the firm body of my horse and look hesitantly up at Omar in the canoe ahead. “Let go and float like a crocodile,” he instructs over the heavy grunts of the horses and the tumultuous splashing of the river underfoot.

We’re in the Argentinian wetlands, crossing the waterways bareback on horse with our rucksacks and Omar steaming ahead by canoe. I’ve been living in Argentina for 10 years and had always been enchanted by stories of gauchos swimming with their horses in the east, but this is far more surreal than any imagination.

As I feel the horse now treading water rather than river silt, my legs discharge behind me. I slide my left hand down to the tail bone, and take a firm hold – aware the coarse mop of horsehair is now my lifeline. I let the trunk of my body float, trying to imitate the drifting caymans that line the shallow waters, while my right arm paddles in a pathetic attempt to keep up with the speed of the magnificent horse swimming in front. I feel both overwhelmed and insignificant in the wide and wet landscape. As the warm river waters reach my ears, I look towards Ruben, who is effortlessly swimming with three horses.

Mingo, a local canoeist who only speaks native Guarani, glides past on the left with his two young children. The waters being to feel calm again as the horses move well and truly out of their depth and mine.

Life as a gaucho in the wetlands is one of watery isolation. Spanning over 15,000km, the Esteros del Iberá is the world’s second largest wetland. Gauchos can rear their cattle only on the highlands in between the waterways. Crossing rivers and floodplains is part of the daily commute.

The gaucho apparel here reflects the wet, isolated and sunny environment: loose shirts and wide-brim hats, homemade leather lassos and always riding barefoot.

They say that the true gauchos of Argentina are made in the east. The constant and perilous threat of flies in open flesh wounds makes for a full day’s work herding the fast and stubborn cows together for treatment. A gaucho here has to run, chase and swim from dusk until dawn.

It’s no surprise, when we reach La Pampa and Patagonia the following week, that many of the gauchos we meet are from the east. Working the land in dry conditions is a godsend and an early retirement compared to the vigour required to survive the wetlands.

San Antonio de Areco in La Pampa feels like a faded gaucho heartland. Here, the gaucho tradition ran so strong it inspired poetry and novels throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. But today, just 80km from the cosmopolitan capital of Buenos Aires, real work in the campo is drying up.

Estancias are turning to soybean production rather than cattle, and the true gauchos – who can read a horse but not words on paper – are left without work.

I sit and talk with some of the men around the dusty town. They complain that nowadays they aren’t allowed to arrive at the bar on their horse, and that the children and women have moved to the city as there is no work in the fields. The city is no place for a gaucho, so they remain. A gaucho and his horse share a stronger union than wedlock.

Almost every gaucho we meet has broken their back at some point. Oscar “La Mosca” (The Fly), who now spends his days playing music for tourists, has broken his back three times falling from a horse. I ask him if he still rides. His 76-year-old eyes brighten like those of a young boy. “Of course; that’s why they still call me The Fly. I stick to my horse better than any fly you’ll meet.”

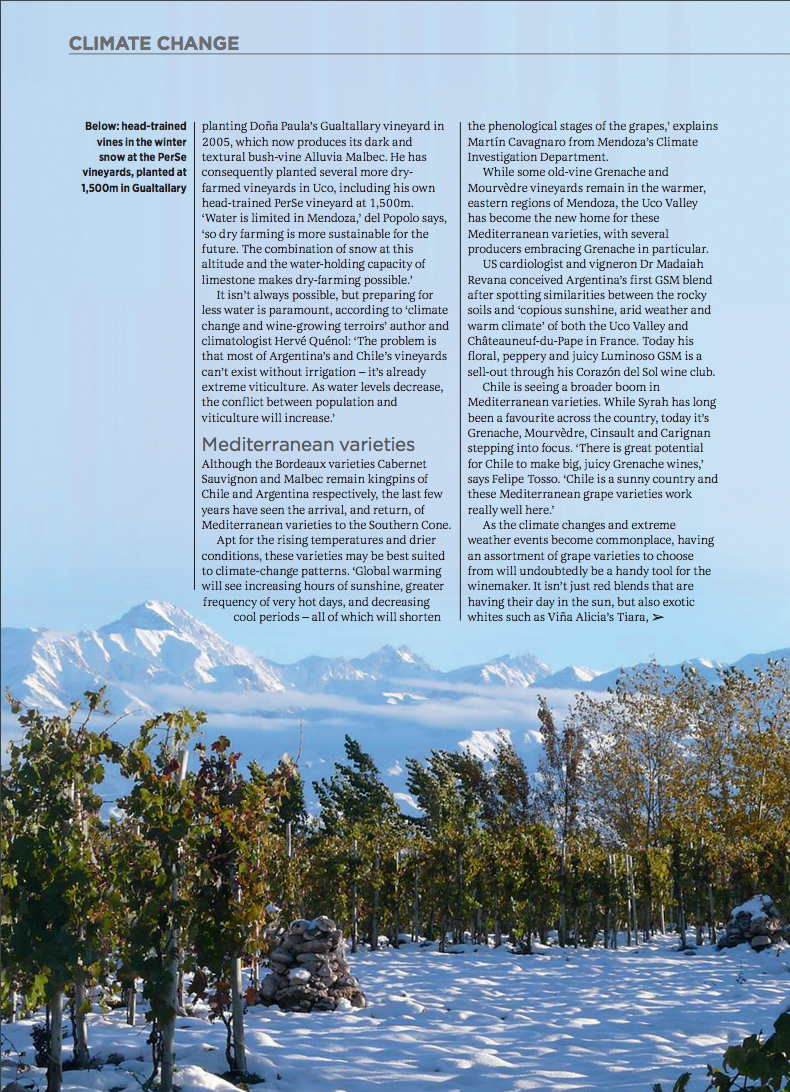

In the depths of the Patagonian steppes and mountains, the gaucho is also a dying breed. Land conservation favours tourism over cattle rearing. Sheep processing plants are abandoned, with only the entrenched odour of sheep faeces as testimony to the Patagonian estancia heyday. Patrons are allowed to have perhaps a hundred cattle for their own use, but the days of gauchos working in estancias with herds of thousands are over.

At one estancia we ride deep into the mountains with a gaucho, to see the glaciers and drink mate tea. I ask him if he enjoys being a tour guide. He shrugs. “It’s a job, but not life.” “Where can you still live as a true gaucho?” I ask. He responds, with a nod towards his homeland: “In the east, or out of sight.”