Patagonia: South America’s new frontier. Decanter 2019

Written for Decanter Magazine, October 2019 In the last decade, winemakers in Chile and Argentina have moved beyond what was seen as the final frontier for South American viticulture — into the cool climates and wild terrains of Patagonia. Growing confidence and expertise; a quest for lower temperatures and greater water availability in the face […]

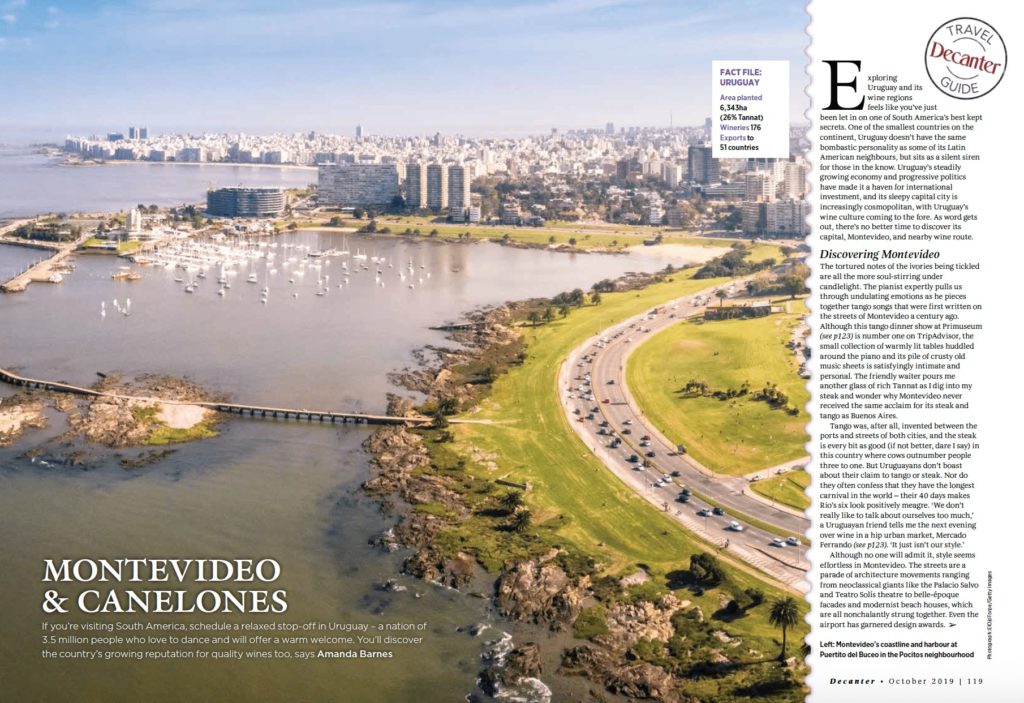

Exploring Montevideo & Canelones in Uruguay

Written for Decanter Magazine, October 2019 Exploring Uruguay and its wine regions feels like you’ve just been let in on one of South America’s best kept secrets. One of the smallest countries on the continent, Uruguay doesn’t have the same bombastic personality as many of its Latin American neighbours but sits as a silent siren […]

Understanding Sherry’s new regulations

Jerez-Xérès-Sherry is the oldest Denomination of Origin in Spain, established in 1935, and its wines and those of the Manzanilla de Sanlúcar DO are today defined as fortified wines (vinos generosos). Both DOs appear to be set for a rehaul as an amendment to allow nonfortified wines into the category has reportedly been passed by the European Commission […]

A Croatian Odyssey: Decanter special

Published in Decanter magazine, July 2019 The diverse regions of Croatia offer plenty for wine tourists to enjoy. Join Amanda Barnes as she tours the Croatian Uplands, Slavonia and Danube in the north of the country, then head to the coast with Anthony Rose as he travels south, from Istria to Dalmatia. While the coast […]

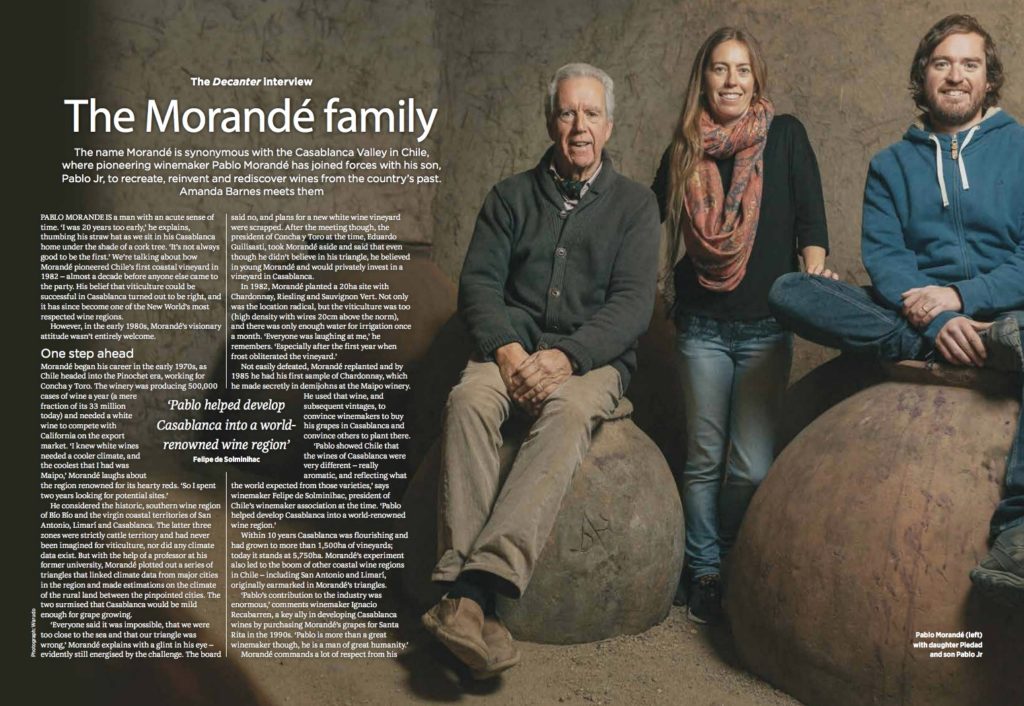

Decanter Interview: Pablo Morande, Father & Son

Published in Decanter Magazine, July 2019 The name Morandé is synonymous with the Casablanca Valley in Chile, where pioneering winemaker Pablo Morandé has joined forces with his son, Pablo Jr, to recreate, reinvent and rediscover wines from the country’s past. Amanda Barnes interviews them (PDF Pablo Morande Interview). Pablo Morande is a man with an […]

Maipo Valley guide for Wine Enthusiast

Written for Wine Enthusiast, February 2019 With massive Andean peaks forming the visual backdrop, the Maipo Valley ranks as one of Chile’s most picturesque spots. It’s also home to some of the country’s top wines. Cabernet Sauvignon is king here, with alluvial flows, a persistently sunny climate and cool evenings creating the ideal breeding ground […]

How to order wine like a pro

Decanter, September 2018 Do your research If you really want to appear like a pro to the rest of the room, do your research beforehand. Most fine dining restaurants have a wine list and menu available online, so scope out potential wines for the meal and identify any dishes that present wine pairing triumphs or […]

The ‘Criolla’ wine revival: a taste of South American wine history

The oldest grape varieties in South America have been sidelined for the past hundred years, but a new generation is now reclaiming its lost winemaking heritage as Criolla varieties re-emerge from the shadows. Amanda Barnes has the inside story… Published in Decanter Magazine, October 2018 When the Spanish first conquered the Americas in the 1500s, […]

Interview: Daniel Pi

Never more comfortable than when breaking the winemaking mould, the Peñaflor veteran is a central figure in the story of Argentina’s wine industry, as Amanda Barnes reveals in this interview with Daniel Pi… Published in Decanter magazine, October 2018 Overseeing the production of more than 200 million litres of wine each year, Daniel Pi doesn’t […]

Chile Vintage 2018 Report

Timing of the harvest was back to normal, a relief following the hot and early harvest of 2017, and maturation periods were steady without any extreme events. ‘We had a cold and wet winter,’ De Martino winemaker Eduardo Jordan told Decanter.com, who produces wine around the country. ‘A warm spring brought excellent bud break. The moderate and […]